Welcome to Hard Refresh

A newsletter about society's reckoning with peak online and digital saturation — and what comes after

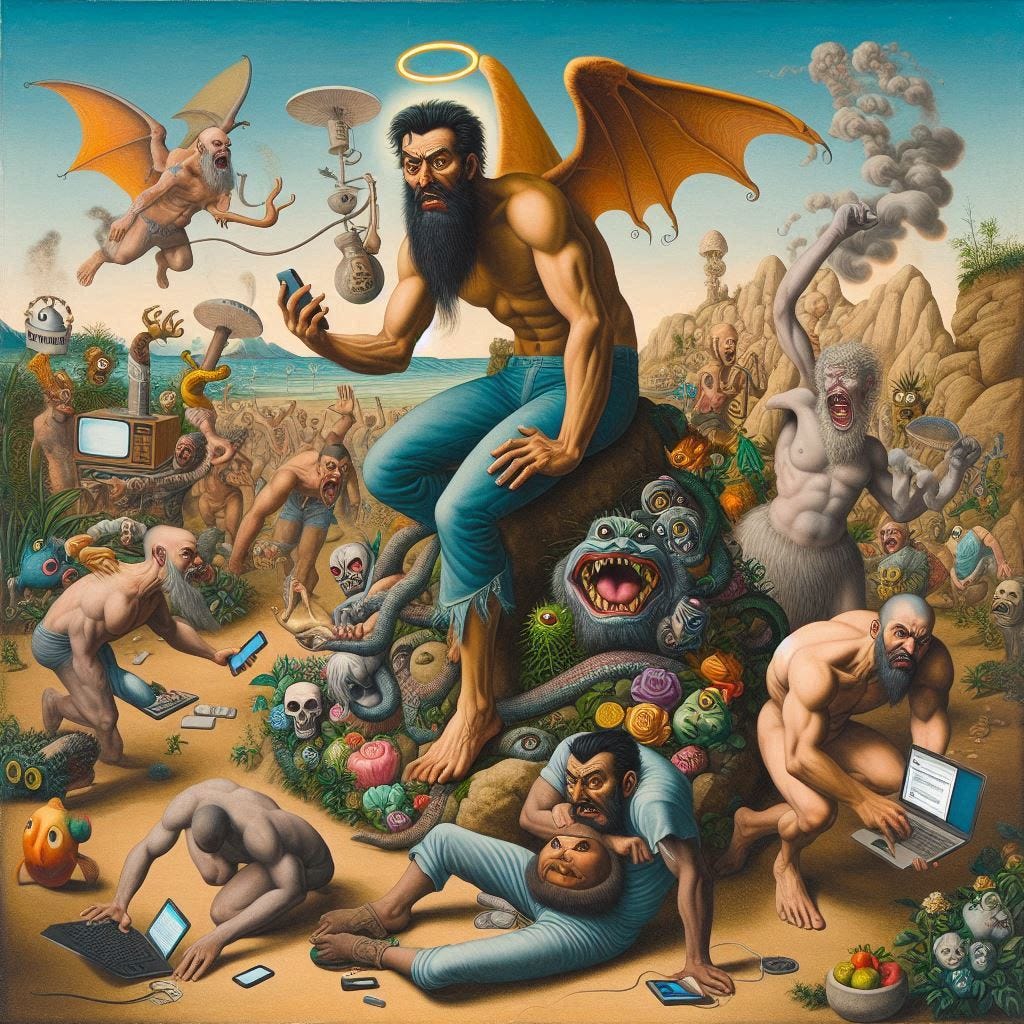

If you’ve been paying any attention to online culture recently, you’ll know it’s a shitshow out there. And I’m not talking simply about a hyper-polarized electorate. I mean the whole thing, the entire full-body, 4D acid bath of living almost every conscious moment of our lives extremely online, immersed in the upside-down, funhouse-mirror logic and values and imperatives of the attention economy.

What, as recently as 2010, felt like a free-thinking communal sanctuary from the predations of corporate America has become a homogeneous, frictionless commercial panopticon that shovels algorithmically amplified, search engine-optimized junk “content” at us from every direction, content whose only purpose is to grab our attention as effectively as possible and keep it for as long as it can.

I’m not the only one who’s noticed this. In fact, it’s become pretty obvious that we as a society have reached a tipping point around all things internet. We’re at the top of a pendulum arc, if you like, and we now find ourselves on the downswing, a new trajectory characterized not necessarily by a mass defection from screens (although that’s very much on the table in some corners), but by something much more interesting: a proliferation of creative new ways of being online, of mitigating the worst aspects of unlocking our phones, of connecting with others, of navigating the attention economy, of pushing back against surveillance capitalism and filter bubbles and the whole notion of being extremely, helplessly online.

This is not altogether new. Over the past 15 years or so, you’ve probably noticed that the way we talk about online culture and the companies that control the places where that culture happens, as well as our own relationships to it all, has shifted profoundly.

Fifteen years ago, in 2009, I was living in Southeast Asia, teaching a course at the Singapore Institute of Management, and at the Royal Melbourne institute of Technology’s Vietnam campus, called “Asian Cybercultures” (later wisely renamed “New Media, New Asia,” after “cyber”-everything fell deeply out of fashion).

In 2009, it was easy to feel hopeful, even a little utopian, about the cornucopia of gifts the World Wide Web offered us. Smartphones and apps were still a fun novelty, and the new social networks of Facebook and Twitter seemed to be enabling all kinds of fresh communal spaces and purposes, even facilitating regime-toppling protest movements in what was dubbed (optimistically, if wrongly) “the Arab Spring.” User-generated content had upended the stranglehold traditional media outlets had long maintained on information, and suddenly anyone could be a reporter — or a filmmaker, or a podcast host, or a music star, or an author with tens of thousands, even millions, of readers. People could suddenly collaborate in ways, and in numbers, previously unimaginable. The democratizing effects of the web and newly available audio and video digital technologies had ushered in an explosion of creative new forms and genres, from remixes and mashups to memes and fan art. It was a heady moment.

“In 2009, it was easy to feel hopeful, even a little utopian, about the cornucopia of gifts the World Wide Web offered us.”

In the course I taught, we dug deep into all of this, as well as the countercultural origins of the web, the rise of social media and digital communities, remix culture, the ease of online anonymity, and the perils and challenges of censorship in the internet age. And we discussed how all of this was influencing power, politics, pop culture, economies, relationships, civil society, and concepts of both individual and national identity, both in Asia and elsewhere. I even published academic research in 2011 on the ways people in authoritarian countries were using memes to subtly popularize criticisms of their governments and public officials.

The overall vibe was that the internet was a profound and revolutionary force for good that would liberate, uplift, and improve the lives of billions.

It all sounds so naive now.

The decade and a half since then has seen the internet evolve — or is mutate the better word? — in ways few of us could have foreseen.

The major tech platforms leveraged their scale and the extraordinary capital they’ve been able to amass through monopolistic network effects and targeted, personalized advertising to become the most powerful and profitable businesses the world has ever known.

“It’s become increasingly clear that we — not advertisers, and certainly not the platforms themselves — are the product in the new social contract the attention economy has birthed.”

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, passed in 1996, has given those same platforms absolute carte blanche to publish and amplify any content their users can dream up, no matter how noxious, false, or inflammatory, without a shred of accountability for any of it.

The tech giants’ unprecedented size, and the fact that the federal government essentially ceased enforcing antitrust law for those same 15 years, meant that those companies were free to either gobble up or crush any competition to their market share with impunity, further solidifying their hegemony over the economy, lawmakers, regulators, and, most meaningfully for our purposes, their users.

Over roughly the same period, the nascent field of User Experience (UX) Design supercharged the science of making these platforms ever more frictionless, engaging, and unputdownable. A legion of skilled UX designers and product managers leveraged deep user research and well-established usability heuristics with previously esoteric principles of cognitive science, behavioral economics, and human-centered design to assure that sites and apps from Amazon and Instagram to YouTube and Pornhub drew us in and kept us there on a drip feed of dopamine and intermittent rewards, where they could monetize our eyeballs to their hearts’ and shareholders’ content.

In the meantime, Big Tech’s aims have continued to move further and further away from a focus on the customer in favor of “growth” at all costs, the customer be damned — a downward spiral Ed Zitron calls the Rot Economy, David Brooks dubbs the “junkification” of American life, and Cory Doctorow has memorably described as Enshittification.

But as the internet has changed, and our experience on it (and even off it) has deprecated, we’ve noticed — and we’ve become more and more pissed off, even as we find ourselves weirdly unable to unplug.

An ambient “techlash” against the titans of Silicon Valley has been building since at least the 2010 publication of Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains. Over the 14 years since then it’s become increasingly clear that we — not advertisers, and certainly not the platforms themselves — are the product in the new social contract the attention economy has birthed, a contract whose primary purpose is to capture, divide, and surveil us in the service of getting us to buy ever more crap. Or, as visionary technologist and author Jaron Lanier has bluntly put it, to make us willing slaves to Big Tech’s “behavior modification empires.”

Meanwhile, the pace and the volume of our dissatisfaction, and the evidence of the harms we’re being subjected to, have ticked up a notch every year since.

The internet itself is now awash in formal and informal stratagems for resisting the power it has over us and reasserting some shred of control over our lives, an open acknowledgement that we no longer feel in control.

The shelves of app stores, for example, are bursting with tools that promise (the irony is almost too rich) to help us block apps and stop scrolling.

The Subreddit r/nosurf is among the top one percent of Reddit forums by size. NoSurf describes itself as “a community of people who are focused on becoming more productive and wasting less time mindlessly surfing the internet.”

The explosion in popularity of mindfulness and meditation over recent years is an obvious response to our fractured experience of the persistent clamor and chaos of always-on internet culture.

Or consider the viral popularity last year of the “dopamine detox.” Influencers glommed onto the fact that the neurotransmitter plays a crucial role in keeping us clicking and scrolling (see “cognitive science” above), and the fasting fad took off (despite being wholly without scientific merit, to no one’s surprise), promising unmatched happiness, greater productivity, academic success, and of course buckets of money. Typical YouTube headline: “Dopamine Detox | How to Regain Control Over Your Life.”

Last year also, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy declared that an epidemic of loneliness among Americans, fueled in large part by our online habits, constitutes a public health crisis. This past June, Murthy went further, urging Congress to pass a law requiring social media platforms to include a warning label, similar to those that appear on tobacco and alcohol products. Among his many justifications was this: “We are in the middle of a national youth mental health crisis, and I am concerned that social media is an important driver of that crisis.”

Three months later, in late September, 42 state attorneys general got on board, asking Congress to act on warning labels in social media, citing the surgeon general’s report. Just this month, 13 states and the District of Columbia sued TikTok, accusing the company of creating an intentionally addictive app that harmed children and teenagers while making false claims to the public about its commitment to safety.

Maybe you have a child who’s back at school this fall, struggling to adapt to new rules in many U.S. schools prohibiting the use of mobile phones in classrooms. That’s happening globally, a reaction to overwhelming scientific and anecdotal evidence that phones are both a powerful distraction to kids and a prime driver for bullying, poor self-images, and worsening mental health.

Or take online dating. For at least a decade it’s been the defacto way for singles of every age to meet a romantic partner, from a one-nighter to The One. But recently a broad swath of those incumbents seem to have hit a wall, particularly among Gen Z. A recent Forbes Health/OnePoll survey found 79 percent of Gen Z respondents have had it with dating apps. On TikTok, viral videos are now urging Zoomers to delete Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge and try to meet people — gasp — offline.

The even more interesting part? Real-world speed dating is seeing both a revival and a reinvention. Luvvly Dating, for instance, wants to make the tech we’re all immersed in a part of the experience, a metaphorical blankie for digital native participants, who show up and follow personalized phone notifications throughout the IRL experience — what’s described as “a flirty scavenger hunt that leads you through a series of mini first dates.” Luvvly dating is now hosting events in five US cities, with plans to roll out to more.

I could go on — the meteoric splash made by the Emmy-awarding-winning documentary The Social Dilemma in 2020; the dozens of state attorney generals who’ve sued Meta for, they claim, knowingly addicting children; the skyrocketing sales for “dumb phones” without access to the internet, and on and on.

But the throughline here is plain. Our honeymoon with Big Tech is well and truly over. Disaffection and fatigue around the internet and online platforms, and their increasingly obvious manipulation of us, our children, our economy and our democratic institutions for their own ends has reached a critical mass. And, as with all such inflection points, it is creating space for something else.

I call this turn a “hard refresh” — a clearing of the grim metaphorical cache that’s accreted over roughly the last 15 years, making way for an entirely new perspective on what it means to be connected.

The purpose of this newsletter, therefore, is twofold:

1. Document our reckoning with what has begun to feel like peak digital saturation.

There are few objective measures out there that track this sort of thing, and we’re certainly not going to hear of it from the platforms and app-makers themselves, who have an existential interest in keeping us online and scrolling. To a certain extent, this is also true of the most news media outlets, who are just as slavishly reliant upon these platforms, and to capturing our eyeballs, as the rest of the web in the attention economy.

But I believe the truth can be found, as always, in what’s happening on the ground, among the ordinary people and communities who live with these tools and platforms and devices. And that’s where I’ll be looking most carefully.

2. Write about what comes after this moment.

I want to call attention to and celebrate the ways people and communities everywhere are beginning to recognize, push back against, and even exit this downward spiral in ways that are human-centered instead of technology-centered, and which are meant to be more real and authentic, steering us away from the metrics of mere “engagement” and toward more meaningful outcomes that prioritize not shareholder profits but what people (not mere “users”) truly want and value.

Not everything will be so mission-driven, of course. I don’t know the organizers of Luvvly Dating, for example, but my guess is they are impelled less by an ideological rejection of swiping, and more by a savvy business response to a behavioral trend they’ve spotted and believe they can bend to their advantage. Hey, I’m not judging.

For several years I’ve followed a host of smart people who are uniquely plugged in to this issue and have exceptionally informed opinions about the downsides of our extremely online existence.

That group includes prime movers like Tristan Harris and Aza Rezkin of the Center for Humane Technology, who produced 2020’s The Social Dilemma and have testified before Congress multiple times on, for example, how algorithms are able to influence people's choices and so effectively change their minds.

I’ve mentioned Nicholas Carr’s groundbreaking 2010 book The Shallows, but scores of similarly skeptical and rigorously reported books and resources on the subject have emerged since then. Former Washington Post reporter Catherine Price’s 2018 book How to Break Up with Your Phone: The 30-Day Plan to Take Back Your Life remains one of the best personal resources out there (and her closely related Substack How to Feel Alive is worth its weight in gold).

Visionary technologist Jaron Lanier’s 2019 manifesto 10 Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now was especially prescient in articulating, five years ago, what has become almost conventional wisdom about these platforms today: that their addictive nature is not an accident or a result of a shameful lack of willpower on their users’ part, but is a carefully designed outcome of the work of thousands of developers and cognitive scientists, who know exactly how to hijack our dopamine-reward pathways (that part, at least, is real) with notifications and features like endless scrolling and the Like button to keep us glued to our screens.

I’ll also follow and report back from people on the front lines like:

Jonathan Haigt, author of this spring’s blockbuster The Anxious Generation:How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness

“Calm Tech” thought leader Amber Case

Digital Minimalism and Deep Work’s Cal Newport

Kyle Chayka, whose book Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture was a fixture in my home early this summer

And of course Taylor Lorenz, who’s just jumped ship from The Washington Post to return to the tech beat she cut her teeth in, this time with her own thing at Substack.

Let me be clear: I don't hate technology. I think the internet is capable of wonderful, extraordinary possibilities. For much of my professional life I’ve been an early adopter of much of the tech that got us into this pickle, and I’ve taught online culture and communication theory at universities from the United States to Southeast Asia and Australia. I’ve helped companies from Microsoft and Nike to Kroger, Starbucks, Slack, Google, Netflix, and Accenture learn and apply the methods and mindsets of human-centered design in the service of digital innovation.

But like many of us, perhaps even most of us, I am troubled by what much of today's online technology is doing to us as individuals, communities, and a society. And I know I’m not alone.

Let’s figure out where to go from here together, shall we?

Absolutely loved this first post from you and super excited to read more. I agree with you - the internet used to be so exciting and now it feels like wading through mountains of nonsense, advertisements and conflated arguments.

Great piece! Can't wait to look into the resources you've mentioned at the end. I'm about 1/3 of the way through filter world at the moment, it's so good.